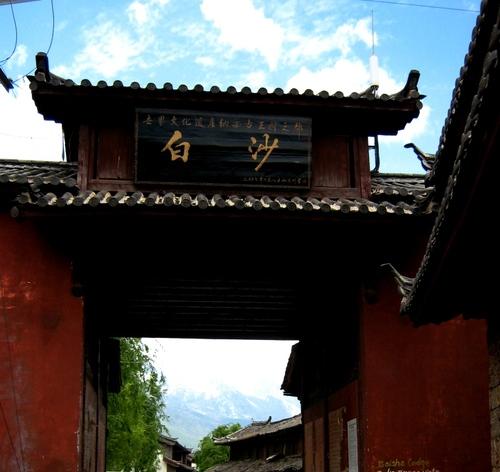

Baisha is a small village on the plain north of Lijiang, near several old temples and is one of the best day trips out of Lijiang. Before Kublai Khan made it part of his Yuan empire(1271-1368), it was the capital of the Naxi kingdom. It’s hardly changed since then and though at first sight it seems nothing more than a desultory collection of dirt roads and stone houses, it offers a close-up glimpse of Naxi culture for those willing to spend some time nosing around.

The star attraction of Baisha will probably hail you in the street. Dr.Ho(or He) looks like the stereotype of a Taoist physician and has a sign outside his door:’The clinic of Chinese Herbs in Jade Dragon Mountains of Lijiang’. The travel writer Bruce Chatwin propelled the good doctor into the limelight when he mythologised Dr Ho as the “Taoist physician in the Jade Dragon Mountains of Lijiang.’Chatwin did such a romantic job on Dr Ho that he was to subsequently appear in every trabel book with an entry on Lijiang; journalists and photographers turned up from every corner of the world, and Dr Ho, previously an unknown doctor in an unknown town, has achieved worldwide renown.

The Baisha Mural

This ancient Baisha murals were stored, preserved and displayed in some ancient buildings in the Baisha village, which is located 10km northwest of Lijiang city. The mural was made from 1385 to 1619, employing the eclectic artist energies of Chinese Taoist, Tibetan and Naxi Buddhists and local dongba shamans. This rich fusion had resulted in a tremendously powerful art, heavy in spirit and awe-inspiring in its presentation of the mystical world. Dominated by black, silver, dark green, gold and red colours, the murals in the back hall, overlaid with centuries of brown soot, are doomladen and bizarre, the scenes and figures, some still vivid in detail, are largely taken from Tibetan Buddhist iconography and include the wheel of life, judges of the underworld, the damned, titans and gods, Buddhas and bodhisattvas. There are trigrams, lotus flowers and even Sanskrit inscriptions on the ceiling. The deliberate damage done to the paintings is apparent and terrible, but the loss of the irreplaceable wooden statuary that filled the temple, of which there is no trace, is even more tragic.